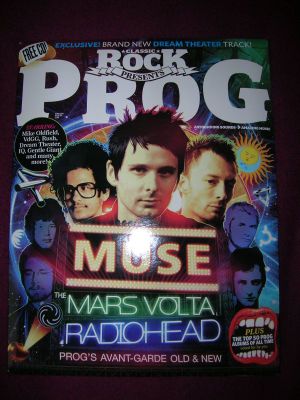

Classic Rock 2009-05-01 – Grand Designs

To cite this source, include <ref>{{cite/classicrock20090501}}</ref>

Issue covering on the progressive rock music genre, including a cover story about Muse.

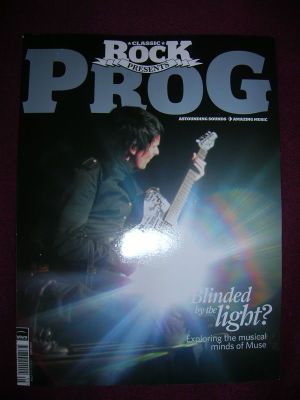

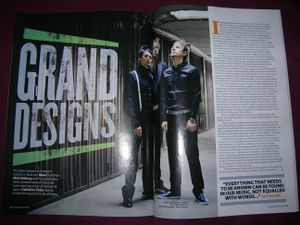

He hates Mozart and doesn’t believe in God, but Muse frontman Matt Bellamy and his bandmates have created some of the most awe-inspiring music of the last 15 years.

It probably shouldn't come as too much of a surprise to learn that Muse recently posted online footage of themselves recording part of their as-yet-untitled fifth album in a toilet. Or that the fruit of such sessions, according to frontman Matt Bellamy, is likely to see the album heading for Classic FM, rather than Radio 1 reception. This is a band, after all, who have spent much of their career demanding the impossible from the most improbable of situations. Where a song could mean a multi-faceted prog meltdown as much as a three-minute pop hit, where instruments could mean guitars as much as they meant animal bones or bubble wrap, and where recording studio could mean mixing desk as much as it meant a swimming pool, or indeed, the lav. All interchangeable entities in Museworld. But while endless column inches have been dedicating to documenting the trio's Herculean achievements, from spotty Teignmouth teens to stadium-stuffing titans, finding out where it all comes from has been a slightly trickier business.

The warning came early enough with the release of their debut full-length, Showbiz, in 1999. Despite the myriad combinations of musical notes available, too many bands have been content to put them through the most standard of groupings. Yet from the white-hot fret-lunacy that erupted halfway through album opener Sunburn, to the Mediterranean lilt of Muscle Museum, the Radiohead-infected Unintended or the pomp and glory of closer Hate This (And I'll Love You), the record showcased a burgeoning vision of rock expression delivered with far more eloquence and proficiency than three lads from a small Devonshire seaside town, barely out of their teens, had the right to be (impressively, Muse wrote songs solely from memory rather than demo. "You can have endless ideas, but you'll probably only remember the ones that were good,” explained Matt. "If you document everything, you can lose your grip on what's relevant/irrelevant.”).

With a self-taught musical ability verging on the virtuosic, Bellamy seemed like the kind of supernerd wunderkind that would be able to reel off catalogue numbers of the obscurest of bands ad infinitum. As it was, the singer, who boasted only a C-grade in music A-level, preferred to make his own music rather than listen to other people's and struggled with simple genre terms. The fact that his father George was a member of 60s surf-psych outfit The Tornadoes who had a Number One hit with the Joe Meek-produced Telstar, or that his childhood was spent in front of an Ouija board provided as much or as little clue as each other. During sessions, producer John Leckie recalled how he had nicknamed one of the Showbiz numbers as ‘the blues song' only for a puzzled Matt to reply,”why do you call that the ‘blues song'? What is ‘blues'?”

Then, it seemed that matters of classification, particularly that of other people's music, held little interest for the frontman. As did providing too much insight on his own.

"Everything about me that needs to be known can be found in the music, and it's difficult for me to equal that in words,” Bellamy explained, going on to argue that, if he could, there'd be no need to make the music in the first place, and that it's important to retain some sense of mystery. "If I say anything that's too open about myself, then people will go, ‘oh, that's what it's all about'.” Perhaps for this reason he was loathe to admit that, secretly, he was a bit of a Rush fan.

Still, by the time the follow-up to Showbiz appeared in 2001, one thing was obvious: Muse were expanding their progressive streak by a Technicolor mile. Origin of Symmetry was a fuel-injected fantasia of neo-classical overtures, psychotic psychedelia and face-hugging rock bliss that cared little for English creative reserve and less for convention. The evolution was helped in no small part by the discovery – and subsequent consumption – of a fieldful of magic mushrooms growing next to the studio, and the fact that Dave Bottrill (whose clients included Tool and King Crimson) was at the production helm, but the record also showed critically, that prog didn't have to mean writing songs that hit the 15-minute mark. And those who tagged Muse as ‘Radiohead with a Freddie Mercury complex' were only half wrong.

"We started listening to Queen and early Led Zeppelin and 70s rock bands that didn't have a problem expressing themselves – balls-out, expressive over-the-top-rock,” said drummer Dom Howard. "So we definitely looked to Queen. We started trying to understand how they could make such epic, massive songs and only be three minutes long.”

The new sounds were kicked off by a song called New Born, which provided a neat handle for Muse's collective mindset and increased success. Certainly there weren't any other albums that year that contained a sci-fi pop Top 20 hit (Plug in Baby) a brooding, hymnal monolith played on the largest church organ in Europe (Megalomania) and what sounded like the Universe exploding inside a Steinway (Space Dementia). The latter's leap into ivory-tinkling hyperspace was the result of some back-to-the-drawing-board thinking from Matt.

"I've tried to push myself to learn new things, be it on an instrument or whatever,” he said. "I played the piano, but I didn't start progressing until after Showbiz. I am influenced by a fair bit of classical music, but when I say that, people think of Mozart, and I hate Mozart. The stuff I'm into is early 19th and 20th century where it's pushing the extremes of the instruments of the time.”

Whether he inspired a generation of Nirvana and Rage Against The Machine fans to go and stock up on the works of Beethoven and Rachmaninoff is debatable, but as Coheed and Cambria and The Mars Volta were discovering, eye-watering vocal histrionics and sonic freak-outs were becoming increasingly commercially viable entities, while the billowing silk pantaloons, gigantic glitter globes and instrument trashing that defined Origin's accompanying world tour brought a sense of spectacle back to modern arena rock.

Metallica were already using New Born as a pre-gig warm-up song, and Bellamy and Co were seeing increasing numbers of Slipknot T-shirts at their gigs, but 2003 saw Muse deliver their heaviest vision yet. Absolution was where Muse embraced the P-word in all but name. It was a concept album – Pink Floyd chose The Wall, Muse, the end of the world. They also chose Floyd's cover designer, Storm Thorgorsen, for the apocalyptically surreal artwork, and had opted for an album playback, Dark Side of the Moon-style, at the London Planetarium.

Songs like Butterflies and Hurricanes and Apocalypse Please found themselves described in terms of War Of The Worlds and Ben Hur, while the record saw the band make it as headliners on Glastonbury's Pyramid stage the following summer. Epic, even by Muse standards.

Though personally he was split between apathetic resignation at impending global disintegration and unabated joy at simply being alive, musically Absolution was an affront to a stagnant rock scene that, with the exception of "amazingly important” acts like Nirvana, RATM, Refused and Tool, Bellamy had considered to have languished in its creative indifference for far too long.

"Rock, strangely enough, has been one of the most conservative genres around, and it's meant to be the opposite,” he explained. "It's been a relatively simple formula since the 70s and few bands are willing to push away from that. If you look at the most successful bands in rock from the last 10 years, they don't touch upon an ounce of creativity of rock from the 70s.” Musical weight for Matt came from elsewhere. "I recommend everyone out there to listen to Romeo and Juliet by Prokofiev. It's one of the heaviest pieces if music you'll ever hear. I think maybe it's because some bands have had such massive success that it's like a big, golden carrot; if you stick to the simple formula, there's a good chance that you'll be very famous and make a lot of money.”

Such things for Muse then, as now, were never priorities. Not when there was a chance to instigate a little inter-band madness. When Dom Howard said they had intended to "experiment as much as possible” he wasn't exaggerating, as one long-term Muse associate, who now works in mental health, recreated the ‘experience' of schizophrenia in the studio by talking through length of plastic tubing.

"It was quite disturbing,” said Matt of possibly Muse's most bizarre recording session ever. "Sitting down and getting your friends to say improvised things with tubes, whispering into your ears, you get the sensation of multiple voices. Really does your head in. We used a sample of it on Apocalypse Please.”

Despite its flamboyant advances, Muse's Armageddon aria was still neatly confined to a single disc, although Floyd's own double-disc effort doubtless found new listeners whose appetites for indulgence had been freshly whetted.

As 2006's supermodern Black Holes and Revelations appeared to be the culmination everything Muse had learned so far, their two sold-out nights at the newly constructed Wembley stadium the following year seemed vindication of sticking to principles and never abandoning even the most outré of ideas. Anyone who wanted to congratulate them was welcome. Anyone who wanted to call them genius was less so.

Matt: "Musically to say that is an insult to other artists who've done stuff way more challenging than us. It worries me when people perceive this band at the level of genius. People that are genius, I don't know where they are these days.”

Instead, the frontman offered long dead composers as examples – those for whom making music wasn't a means to an end, but, as for Matt, the end itself.

Though he wasn't a particular enthusiast of Bach, or religion in general, Matt could relate to the composer's higher sense of purpose as one who made music for God. So it's perhaps less surprising to learn that last year, he resumed his Ouija board activities from his youth and looked to the other side in the hope of receiving some spectral inspiration.

"A lot of composers weren't making music for money or fame, they were making it for God,” he explained. "I don't believe in God, but maybe there's a part of me that is trying to make music for something that is beyond what I'd ever want to reap any rewards for. It's difficult in the days we're in to be that pure about music. When I get in the studio, I reach a moment where I'm sure I'm onto something, and I really want to follow it through. Next thing I know, I've got to wrap it up and make a video.”